Another page of nekked tomatoes! Who will stop them?

Probably not yours truly...

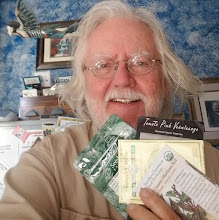

The seed catalogs keep coming and they are all devoured with gusto – I’ve not only already ordered from Pinetree (see a previous post), I’ve gotten the seeds and some of them are already planted (onion and shallot seeds needed to go in ASAP because they really are a little late). The Seed Savers Exchange catalog arrived a couple of days ago and I got to feast my eyes on this year’s beautiful edition of offerings. So gorgeous are the photos of all their delicious vegetables, I find myself drooling and fantasizing about the harvest I’m going to realize when I buy all these seeds: folks, I submit that these catalogs cause such visceral reactions in gardeners that there is no way to avoid calling them “vegetable porn.”

Not that I want to denigrate Seed Savers Exchange; their catalog is one of the highlights of the winter months. The photos are stunning and well done – if you get the catalog, may I refer you to their famous photo of a wagon load of many different squashes spilling out to the ground with a red barn as the backdrop. If you don’t get their catalog, go online and order it – whatever Seed Savers Exchange wants for it is cheap – that one photo alone is worth bankrolling.

But the reason Seed Savers Exchange is important goes much deeper than the gorgeous vegetable photos in their catalog – and if you are not a member, I urge you to consider it. Kind of like, beauty, in this case, is more than skin deep.

Before the modern time, seeds were passed down from generation to generation – a single person or family, might have raised a tomato on that parcel of land for twenty years or more, each year selecting the best, or the earliest or the most disease resistant. As this was done over all those years, the genetic composition of this tomato gradually changed and became more adapted to just that area. This occurred over the entire agricultural world and by the early 1900’s gardeners were privy to a veritable smorgasbord of different varieties of many different vegetables. These varieties were stable hybrids that became what they were over a long period of time, they are open-pollinated and represent a genetic diversity that is one of the truly great treasures of human kind; we now call them 'heirloom' seeds. The world was blessed with thousands of such tomatoes and other vegetables. However, the richness of these differences began to be lost soon thereafter.

On one hand, our food supplies were being put in the hands of larger farms with shipping over longer distances and the operations were being carried by larger corporations and machinery was replacing hand labor as fast as inventors could come up with machines to do the work. The qualities valued were of consistency, uniformity, and shipping and holding ability. And productivity above all else. These qualities were the qualities of modern plant breeding and most seed breeding (especially in the US) was done for the benefit of these large corporations to put veggies in our local supermarkets.

Not only did our vegetables begin to taste like cardboard, which was not important to the large corporations wanting uniformity and shipping ability above all else, the many different regional varieties, with their rich diversity of genetics began to disappear. Losing this genetic diversity is as frightening as leaving our food supply in the hands of a few huge corporations that have nothing more than their own profit as their guiding interest. The potato famine in Ireland, though exacerbated by the politics of the day, had a lack of genetic diversity in potatoes grown in Ireland at that time as a root cause. Once the blight had made landfall on the island, it romped through the entire country without stopping because the two major varieties planted there shared a genetic susceptibility to the blight. Other potatoes, not grown in Ireland, and ignored for food production at that time, were not susceptible to the blight and it was these other potatoes that provided the genetic material for Ireland to be able to resume growing potatoes to feed their population.

On one hand, governments have established seed banks filled with seeds of commercial crops kept in very cold and very dry conditions to preserve some of the genetic diversity for future generations. Every so often, a seed is selected and grown out to provide more seeds for the seed bank. Though expensive, it is one way genetic diversity can be preserved. Typical of a governmental operation, it is expensive and a large, capital-intense operation.

But the other way of preserving this genetic cornucopia is for gardeners all over the world to grow them and keep the genetic lines vibrant and alive – and even creating more diversity by growing different varieties in their own gardens – or even doing their own crossing and coming up with their own stable hybrids. And enjoying the produce in the meantime! Not nearly as expensive while being more diverse and a lot more fun.

A ‘lite’ version, is to purchase from Seed Savers Exchange and allow them to continue their efforts at growing out the seeds – or join Seed Savers Exchange and be a more integral part of their effort. I support Seed Savers Exchange; investigate them and I think you’ll find their efforts essential too.

At $35, it's not that expensive and would make a wonderful holiday present for someone on your list!

david

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment